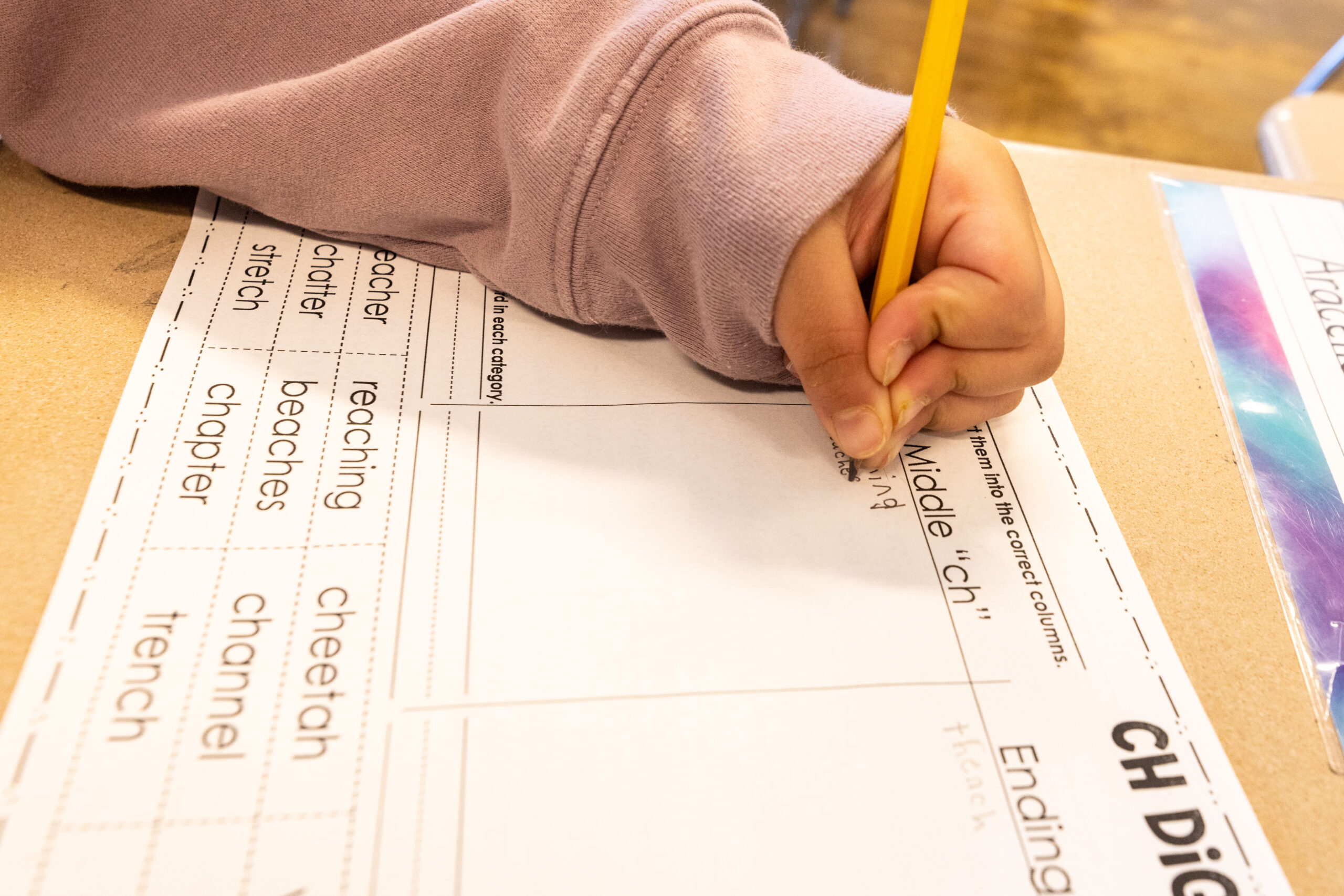

A student manipulates phonemes by using the letter combination ‘ch’ at the beginning, middle and end of a word on a worksheet. (Jo Sittenfeld/Rhode Island Current)

Science-Based Reading takes the guesswork out of learning to read. And that’s a very good thing.

The decades-long war between Science-Based Reading (SBR) and Balanced Literacy (BL) is over. Sound the celebratory bells. Mountains of research backing SBR have finally convinced most education leaders.

Forty-five states have passed laws to mandate SBR reading instruction, including Rhode Island, which passed the Right To Read Act in 2019. While the transition has begun here, the work is far from complete. But before diving into the politics or other complications of making this huge pedagogical shift, let’s look at where we are as a nation and where we’re going.

A June 2023 report, “The Reading Revolution,” has a concise history of the wars, starting with the 1955 publication of Why Johnny Can’t Read, and arguing for SBR. The pendulum swung back and forth, but arcing ever further toward the BL extreme, most famously developed by Lucy Calkins at Columbia Teachers College.

Central to BL is what they call the “3-cueing system.” “Cueing” is really guessing. Reading correctly is secondary to helping the kids feel good about themselves and their abilities. Roughly one-third of all students learn to read without much trouble. Cueing nurtures that same wholesome efficacy in the other two-thirds. For a while.

According to the National Assessment of Educational Progress, nationally 32% of public-school 4th grade readers are proficient. In Rhode Island, it’s 34%. We’re only successful with that same one-third.

At BL’s worst, when the written word is “cat” and the kid uses the cues to read “kitty,” close enough. If the kid says “beach” for “sand,” that’s great.

Except that it’s not.

By the 4th and 5th grade, as the content becomes less familiar and harder to guess, the happy, skillful feeling disappears. Poor readers can’t build new content vocabulary to expand their reading skills, never mind build their knowledge base.

Even Lucy Calkins has recanted.

Mind you, we don’t want to lose BL’s passion for teaching kids to love literature. But we also can’t dismiss foundational skills as “drill and kill.” Learning often includes some tedious practice – like playing scales to learn an instrument, or memorizing math facts.

Reading is not a natural human function like learning to talk.

Science-based reading uses specific instruction, practice and assessment for five streams of skills and knowledge. This ensures that all kids have the toolbox that allows them to tackle any age-appropriate text. Those streams are:

Phonemic Awareness – The ability to isolate, hear and work with the individual sounds within human speech. The understanding that phonemes, the smallest unit of speech, get strung together to become different words. Nursery rhymes are helpful: “Higglety pigglety Pop; the mouse has swallowed the Mop,” etc.

Phonics – The ability to associate the discreet sounds of words – the phonemes – to written letters and words – graphemes. The written phoneme “at” can be combined with other letters for “cat” or “sat.” Words on a page use sounds (“at”) to make increasingly complex words. Without phonics, struggling readers can’t “decode,” which is to say, sound out unfamiliar words by blending the written phonemes into words. Granted, far more than other Romance languages, English is rife with anomalies like “gh” in “enough,” which sounds like “f” as in “fish.” Still, the basics come first.

Vocabulary – The ability to make meaning of words as a result of increased background knowledge. Sounding out meaningless words builds frustration, not skill. So kids need deep, quality content and experiences that use words and concepts to build knowledge and by extension, reading skills. Best to read a book about the ocean; go to the beach (as every Ocean State kid should); then read a book about sharks. The repeated oceanographic words and concepts will take root and grow into understanding similar words and concepts in other fields – “current” for example. (Side note: The size of someone’s vocabulary correlates strongly with Intelligence or IQ. IQ is not fixed, but can be built with vocabulary.)

Comprehension – The ability to intuit and learn the underlying grammar and structure of language. This presupposes the ability to decode and know the meaning of words. Kids comprehend when the string of words becomes a coherent, intelligible sentence. With comprehension, those sentences gel into memorable content.

Fluency – The ability to pull together all of the above with age-appropriate speed, most easily assessed by having the kid read out loud. How often does she stop to decode words that are still unfamiliar? Can the kid read many of the words by sight, the way mature readers like you and me power through texts? At the end of the day, fluency is what gives kids, and adults, a genuine sense of reading mastery.

We can’t lose the high value BL put on love of literature. We also can’t sacrifice real skill to a feel-good strategy. Skillful reading is everything in education. Everything. In all subjects, even sports and arts.

Still, telling teachers to forget much of what they learned in grad school and develop new habits is a big ask. New, more fun curricula are emerging, but ensuring that the basics become second nature might involve some less fun teaching and learning.

We need to retool 14,000 public school districts, 98,000 schools and 3.2 million teachers in order to reach the unlucky two-thirds.

The lift is huge. But over time, the payoff will revolutionize public school efficacy. The poorly-served readers will finally experience happy, self-esteem feelings for real.

First published: RI Current News, Novembwer 16, 2023

Public comments posted on this site are much appreciated. However, if you prefer: [email protected]