Children who learn to identify letters and sound out words are much more likely to succeed as they develop reading skills. (Jo Sittenfeld/Rhode Island Current)

Are those kids lounging with books in bean bag chairs actually reading?

Public schools in the U.S. have inadvertently dug themselves into a deep hole of bad reading instruction. The hole is so deep, states have recently passed about 200 reading-instruction laws to speed the drastic changes needed to turn around this educational Titanic.

For decades, researchers and advocates implored schools to apply the science behind successful reading to classroom instruction – called Science-Based Reading (SBR). During those decades, schools instead used the very different techniques of Balanced Literacy (BL). Those were the two camps of the “reading wars.” At last, a critical mass of educators and the public loudly lamented that the ineffectiveness of BL left roughly two-thirds of K-12 students unable to read proficiently.

Five distinct but related skills must come together to develop the ability to read. None of those skills are adequately addressed in BL. So when educators talk about a “reading revolution,” they’re not kidding.

Sadly, new educational initiatives have rained down on school staff so often, it’s no wonder they developed a “this too shall pass” attitude. But education dollars have been squandered on a grave social injustice against those struggling readers, creating an urgency that moved states to turn to the heavy hand of the law.

But how did we get here?

In 2022, education journalist Emily Hanford blew the lid off the reading wars in her six- podcast series “Sold a Story.” She takes you into the down and dirty of, for example, the princely profits reaped by a textbook publisher and its curriculum-writing stars.

I’ll borrow two of her stories, starting with a window into one typical BL lesson observed by a mom in South Kingstown. As we locals know, South Kingstown is the home of the University of Rhode Island and one of the most reputable school systems in the state.

In 2019, this mom’s eldest child started first grade. The school sent home easy books for them to read together, but the child insisted that his mother read the book repeatedly before he’d even try to read it out loud. Was he memorizing the words and not reading at all?

Hanford has a video showing a teacher demonstrating the same lesson the mom had seen. In the video, the teacher reads along with her students until they come to a word covered with a sticky note. The full sentence describes two kids who ran away and now worry that their parents will [sticky note] them.

Punish? Scold? No.

So the teacher guides the students through BL’s guessing system but finally has to suggest the word “miss.” She peels off the sticky note, revealing the word, and then walks the class through BL’s “triple check.” Does it sound right? Look right? Make sense?

They worked on everything but the word.

Such strategies greatly troubled doctoral student Marie Clay in the 1960s. So, for her dissertation at the University of Auckland in New Zealand, she observed and wrote about how good readers acquire their skills. Good readers, she found, kept building skills while poor ones only got worse. (Hanford cites Clay’s work as the origin of BL.)

Good readers were like detectives, solving problems by looking for clues. They didn’t sound out words, except as a last resort. Instead, they investigated the text to figure out what an unfamiliar word might be.

Three strategies emerged:

- Semantic – Good readers gleaned clues about unfamiliar words from the context of the story itself, including its pictures.

- Syntactic – They skip past an unfamiliar word until they’d read the whole sentence to see if the grammar suggested what word would sound right.

- Grapho-phonemic – They consider the first letter of the word to see if it gives a hint.

Clay compared her techniques to playing “20 Questions.” Keep guessing, and you’ll get it.

Later research found that only one in four guesses were right.

To help the struggling readers still left far behind, Clay created a remediation program called Reading Recovery, which is basically BL on steroids. Reading Recovery persists in many schools because it does improve reading in the short run. A highly-trained teacher spends 30 minutes a day with one reader at a time, for about 10 weeks, at the cost of about $10,000 per kid. At those prices, low-income schools can’t afford such remediation.

As struggling readers get older, they increasingly dislike reading because it’s hard and baffling, a magic art whose tricks elude them. The percent of proficient 4th grade readers hasn’t changed in decades.

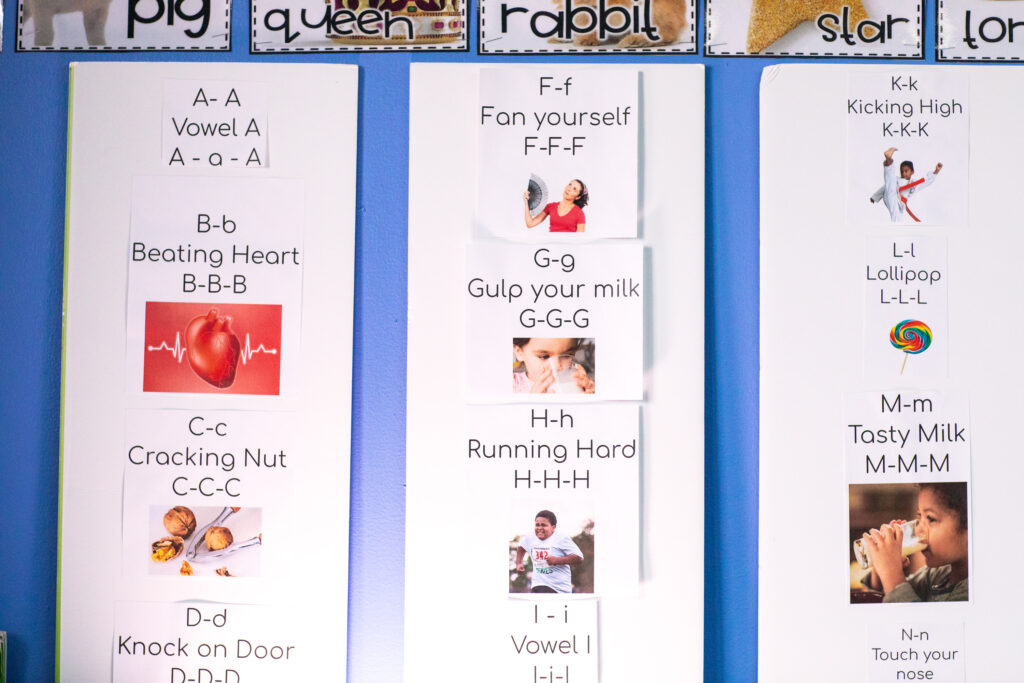

Balanced Literacy has great optics. I’ve seen classrooms with kids lounging on bean bag chairs, maybe with soft music playing, seemingly immersed in “reading” instead of suffering through the phonics necessary to sound out words. Teachers and kids look happy.

But only some of those kids in the bean bag chairs were actually reading. That is the core problem.

But what now?

Rhode Island has a reading law called the Right to Read Act. Predictably, it’s a wonky read, but greatly appreciated by the SBR advocates. In the new year, I’ll start unpacking what’s in the legislation itself, and how this is playing out in the field.

But be reassured that Rhode Island is underway with making this gargantuan shift.

First published: RI Current News, December 22, 2023.

Public comments posted on this site are much appreciated. However, if you prefer: juliasteiny@gmail.com